C’est une avancée importante qui a été faite par O. Boulle et ses collègues de Spintec et de l’institut Néel à Grenoble en démontrant, dans une étude à paraître dans Nature Nanotechnology, des skyrmions magnétiques stables à température ambiante. Ces structures passionnent actuellement de nombreux groupes de recherche dans le monde, car ils offrent un nouveau moyen de stocker et traiter l’information à l’échelle nanométrique dans les ordinateurs. Cette particule magnétique de taille nanométrique est composée de nanoaimants élémentaires qui s’enroulent de proche en proche pour former une structure spirale très stable, comme un nœud bien serré. Prédite théoriquement dans les années 80, elle n’a été observée pour la première fois qu’en 2009. Trois ans plus tard, deux équipes démontrent que les skyrmions peuvent être manipulés par des courants électriques très faibles, ouvrant la voie à leur utilisation pour stocker et traiter l’information. Plusieurs dispositifs mémoire et logique révolutionnaires basés sur la manipulation de ces skyrmions dans des nanopistes magnétiques ont ainsi été proposés, promettant grande densité d’information et très faible consommation d’énergie. Cependant, ces applications restaient encore lointaines car les skyrmions n’avaient été observés qu’à très basse température ou en présence de forts champ magnétiques et dans des matériaux exotiques loin de toute application.

En démontrant des skyrmions stables à température ambiante en l’absence de champ magnétique, O. Boulle et ses collègues ont ainsi fait sauter un verrou important. Pour cela, ils ont déposé une couche magnétique de cobalt très fine (quelques atomes d’épaisseurs), en sandwich entre une couche de métal lourd (du platine), et une couche d’oxyde de magnesium. Les phénomènes physiques à l’origine de la structure en forme d’hélice du skyrmion ayant lieu aux interfaces avec les métaux lourds et les oxydes, les effets sont ici décuplés. Par ailleurs, la technique de dépôt utilisée, appelée pulvérisation cathodique, a l’avantage d’être rapide et est couramment utilisée dans l’industrie microélectronique.

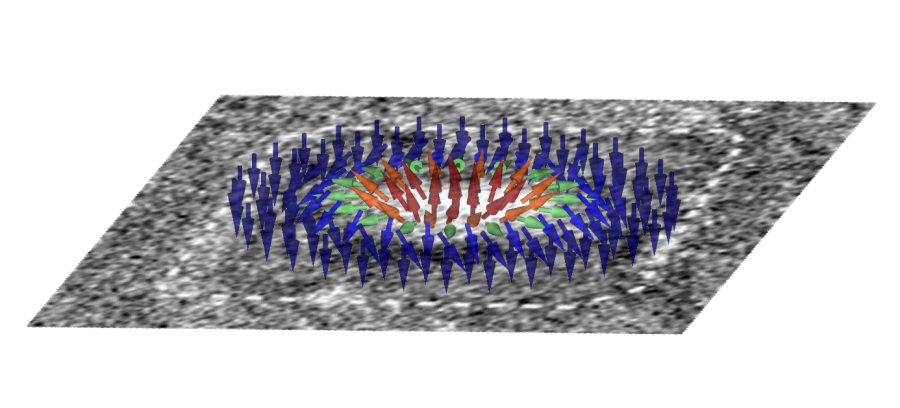

Une fois le matériau identifié, l’étape suivante a été de prendre une photo du skyrmion, notamment de la structure interne en forme d’hélice qui le caractérise. Un vrai défi étant donné la taille minuscule du skyrmion, quelques dizaines de nanomètre. Pour cela, les longueurs d’onde de la lumière visible sont trop grandes et il est nécessaire d’illuminer le skyrmion par les rayons X très purs générés dans les synchrotrons. C’est ainsi à l’aide de microscopes magnétiques très haute résolution « XMCD-PEEM » que le skyrmion et sa structure interne caractéristique ont pu être mis en évidence au synchrotron Elettra à Trieste et Alba à Barcelone (voir Fig.1).

La prochaine étape sera de bouger ces skyrmions à l’aide d’un courant électrique, un pas de plus vers l’utilisation de ces nouvelles particules pour coder et manipuler l’information à l’échelle nanométrique.

Ces résultats ont été obtenus dans le cadre d’une collaboration entre plusieurs laboratoires français : Spintec et l’institut Néel à Grenoble, le laboratoire des sciences des procédés et des matériaux Université Paris 13. Les expériences d’imagerie magnétique XMCD-PEEM ont été effectuées aux synchrotrons Alba près de Barcelone en Espagne et Elettra, près de Trieste en Italie.

Fig. 1 En noir et blanc : Image de microscopie magnétique d’un skyrmion magnétique au milieu dans un nanoplot d’environ 400 nm de côté (tiret blanc). Flèche de couleur : illustration de la structure magnétique du skyrmion.

Fig. 1 En noir et blanc : Image de microscopie magnétique d’un skyrmion magnétique au milieu dans un nanoplot d’environ 400 nm de côté (tiret blanc). Flèche de couleur : illustration de la structure magnétique du skyrmion.

Pour en savoir plus :

•”Room-temperature chiral magnetic skyrmions in ultrathin magnetic nanostructures” O. Boulle et al., Nature Nanotechnology (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2015.315

•”Skyrmion on the tracks”, A. Fert et al., Nature Nanotechnology, 8, 152 (2016)

•”Le skyrmion, mémoire en attente” D.Larousserie, Le monde, 26/08/2013

Magnetic skyrmions observed at room temperature

These nanoscale magnetic structures have been observed at room temperature in materials compatible with the microelectronics industry. These results break an important barrier for the use of skyrmions as nanoscale information carrier in our computers.

It‘s an important breakthrough that was recently made by O. Boulle and this colleagues from Spintec and Institut Néel in Grenoble by demonstrating magnetic skyrmions stable at room temperature. These structures are currently fascinating many research groups in the world, as they offer a new way to store and process information in our computers. These nanoscale magnetic particles are composed of elementary nanomagnets that wind to form a stable spiral structure, like a well tighten node. Although predicted in the 80’s, it has only been observed for the first time in 2009. Three years later, two research teams demonstrated that skyrmions can be manipulated by very low electrical currents, which opens a path for their use as information carriers in computing devices. Several groundbreaking memory and logic devices based on the manipulation of skyrmion in nanotracks have thus been proposed, that promise very large information density and low power consumption. However, these applications still remained distant as skyrmions had been observed only at low temperature or in the presence of large magnetic fields and in exotic materials far from any applications.

By demonstrating skyrmions stable at room temperature and in the absence of external magnetic field, O. Boulle and his colleagues have thus broken a major barrier. To reach this result, they deposited an ultrathin magnetic layer of cobalt (a few atom thick) in sandwich between a layer of a heavy metal (platinum) and a layer of magnesium oxide. The physical mechanisms at the origin of the helical shape of the skyrmion arising at the interfaces of heavy metal and oxides, the effects are here strongly enhanced. In addition, the deposition techniques used, named sputtering deposition, has the advantage of being fast and is commonly used in the microelectronics industry.

Once the material was identified, the next step was to shoot a picture of the skyrmion, in particular its internal spiral structure. A challenge given the tiny size of the skyrmion, several tens of nanometers. The wavelength of the visible light being too large, it was necessary to enlight the skyrmion using the very pure X-Ray generated in synchrotrons. To observe the skyrmion and its internal structure, very high spatial resolution “XMCD-PEEM” magnetic microscopes have been used at the Elettra synchrotron in Trieste, Italy and in Alba synchrotron in Barcelona, Spain (see Fig.1) The next step will be to move these skyrmions using electrical current, a move further toward the use of these particles to code and manipulate the information at the nanoscale in computing devices.

These results were obtained through a collaboration between several French laboratories : Spintec and Institut Néel in Grenoble, the laboratory of process and material sciences, Paris 13 University. The XMCD-PEEM magnetic imaging experiments were carried out in Alba synchrotron in Barcelona, Spain, and in Elettra synchrotron in Trieste, Italy.

Fig. 1 In black and white : magnetic microscopy image of a magnetic skyrmion in the middle of a squared nanodot (white dashed line, approximately 400 nm wide). Colored arrows : illustration of the magnetic structure of the skyrmion.

More reading :

• “Room-temperature chiral magnetic skyrmions in ultrathin magnetic nanostructures”O. Boulle et al., Nature Nanotechnology (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2015.315

• “Skyrmion on the tracks”, A. Fert et al., Nature Nanotechnology, 8, 152 (2016)

• “Le skyrmion, mémoire en attente” D.Larousserie, Le monde, 26/08/2013